“This is the chap they stuck in with Len Such to see what he could extract from Len. Dixon & Bicknell, other members of Hughes’s crew were with us in Stalag IVB. They both said Hughes was queer.”

Court hears alleged statement by freed prisoner

Airman sent ‘bomb Berlin’ message in a prayer

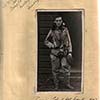

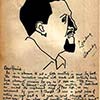

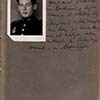

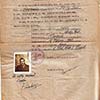

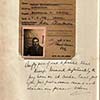

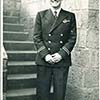

[Photo] Raymond Hughes, he is 23. Eleven Charges. His Badges

Broadcast was in Welsh

Express Staff Reporter: RAF Depot, Uxbridge (Middlesex), Thursday

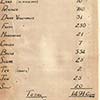

The charges.

There are eleven charges against Warrant Officer Hughes and among them are:

Giving the enemy information about RAF methods used in the raid on which he was shot down. Aiding the enemy by asking prisoners at Dulag Luft I to give the Germans information on RAF formations. Making radio propaganda records. Broadcasting propaganda from Berlin radio. Lending money to those forming the British Free Corp intended for warlike operations against the Russians. Advising the enemy on combating bombing raids on Berlin. Accepting employment at the German Foreign Office. Accepting employment at Berlin Radio. Certain of these offences are punishable with death.

In a 50 page statement read to an RAF court martial this afternoon an air gunner shot down over Germany was alleged to have said that in a broadcast from Berlin to British forces in Italy he broke off a recitation of the Lord’s Prayer in Welsh to say:

“You know where I am. Give the Sports Palast (in Berlin) a good clout. It is being used as a place for talking over the air.” The accused man is a repatriated prisoner, Warrant Office Raymond Davies Hughes aged 22 one of the crew of a Lancaster who baled out at 8,000 feet after bombing the secret German V weapon experimental station at Peenemunde in August 1943. The opening pages of the document which was read by an officer of the Special Branch RAF dealt with the details of the airman’s escape from the blazing bomber and his capture by the Germans on the shores of the Baltic. It was when he reached a prison camp that he was seen by a political interrogator named Lieut Conninghaus. The statement went on: He mentioned to me the name of a fruiterer at Mold, North Wales where I live, called Blondell. He also mentioned the name of the local hairdresser which was correct.

I was later twice questioned by different officials about Pathfinders and I told them I knew nothing about them. Hughes’ account here described how he was flown to a castle south of Bonn and continued: We were shown into a large dining room where the tables were laid with plenty of chicken., champagne and so on. I had a meal there. After the meal I did not get any further interrogation but some of the German pilots asked me various questions in conversation.

Cell unlocked.

Next day we went back to Dulag Luft I where an American and a Pole came to me and asked me if I thought of escaping. I told them that I would escape if I got the chance. After these people left I found my cell door was unlocked and I went out and later walked in and out quite freely. As time went on I got more freedom and was able to get about to almost any part of the building including the offices and registries. Here a lot of the information was photographic copies. When talking to one of the girl clerks one day. I asked her how they got all this information. She told me that their spies in England took photographs of documents and sent them back by radio photography. One day a German officer sent for me, and practically told me to assist in getting Red Cross interrogation forms filled up. He also told me it would be better if I was known as “Herr Becker”.

After Squadron-Leader Carpenter left the camp I lost interest in the work I was doing and told Lieutenant Conninghaus that I wanted to be sent to a camp. I was told that could not be done, as I knew too much. Later I met Carpenter and Zuromski (a Polish Spitfire pilot) in the Aut-Hotel, Charlottenburg. Carpenter warned me that the Germans would try to get me to broadcast, but under no condition was I to go on the air. The next morning a motorcar took me to the Reichsrundfurk. There I was placed in a room and given the Daily Express three days old and told to read it. Later they put me in front of a microphone and told me to read an article. I did so and took advantage of a missing tooth and caused a hissing noise when I read

Not a broadcaster.

The next week I was told I had been found not suitable to broadcast and I had been sent to the Foreign Office to see if I was any good for writing broadcasting material. The same day I was introduced to Baillie-Stewart, a man named Hewitt, a man named Boldey, and a man named M’Carthy. There was a raid on Berlin that night, and owing to damage I did not report till three days later. I was put into a small office next to one occupied by Baillie-Stewart. I was shown some specimens written by Baillie-Stewart and others, and I told him I had no experience or knowledge of that sort of thing. I told Squadron-Leader Carpenter about it, and the attitude he adopted was that it was wise for me to be amiable with the Germans. In all, assisted by Squadron-Leader Carpenter, I wrote three or four of these talks, and got a lot of material out of the book, “John Amery speaks.”

Berlin was being bombed at night. Squadron-Leader Carpenter and I went out and destroyed telephone communications in street kiosks by breaking the wires. In all we estimated that we had destroyed 243. At this time Squadron-Leader Carpenter and I were obtaining information and checking up on people who we believed were to be in German employ.

Offered commission.

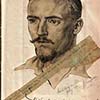

In December 1944, Baillie-Stewart told me I was no good for broadcasting, as I was particularly dumb at writing, and he brought two friends, Collander and McLardy, and said they would like to have a chat. They both told me they were two of the big six in the British Free Corps. So far as I could gather John Amery and William Joyce were endeavouring to raise a British Free Corps on the lines of the Viking Waffen SS which fought against the Russians. They told me they had been ordered to offer me a commission.

I told them it was a matter that would have to have serious consideration. They said there were 2000 waiting to join the corps, and Brigadier-General Patterson of Crete was waiting to take over the corps but he would not do so until it had been properly formed.

I knew what I was doing, and…to encourage them I told them I was interested. I met Squadron-Leader Carpenter by appointment and I told him all about it. He told me I was making a good show and that I must get into the Free Corps, but be careful I did not sign any papers. The bombing of Berlin was then increased to its maximum and I mentioned to Baillie-Stewart that I had not been interrogated respecting British bombing tactics. I told him I had been in Berlin during 20 raids and watched how late German fighters arrived on the scene, the effect of the flak, and convinced him that a target was always attacked from the south. I knew this was not the case as I had done 21 operations over Germany, but it excited him. The same day I was taken by car accompanied by Baillie-Stewart and two Luftwaffe officers to the German Chancellery, and during an interview Goebbels came into the room. I told them that the flak was nowhere near the aircraft, and the night fighters did not get up until the bombers were on their way home. I said the flak batteries were not in proper position, as the flak appeared miles in front or miles behind the aircraft. I also mentioned that the pendant light should be left on as a guide to the night-fighter pilots. I had in mind that the light would be of great assistance to the bombing pilots.

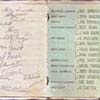

Got signatures.

I decided to try to obtain the signatures of everybody in the Free Corps, and as they were all short of money I arranged a card system on which got all their particulars for money advanced. About this time I was transferred from the Foreign Office and was told I would have another broadcast test and was given a script written by a Briton named Vernon. I tried to make a recording of it but again caused faults in my voice in order to make an unsatisfactory recording.

In January 1944 I wrecked a train bringing workers and material from a tar factory in Berlin. I jammed the points with a brake. I was informed that the train had gone over an embankment and 63 people had been killed. Hughes’s statement concluded with a description of his liberation by the Russians in April this year. The prosecution then read a letter from Hughes to his parents, it said:

Dear Mum and Pop,

Gosh, it’s really grand to be able to write to you once more. Lots of things have been happening to me. There are charges now that I have been wearing German uniform. Please don’t believe I have been a traitor. It is untrue. If you think your son has been a traitor to his country it will finish me.

Secrecy barred.

Then the name of Captain Hans Vollmann, of the Luftwaffe, was called. He marched into court clicking his heels and saluting the President in English fashion. The court decided to hear his evidence in public in spite of a submission by a prosecuting officer that it should be taken in camera, in case secret information was revealed. Vollmann described how he was an interrogator at Dulag Luft I and saw Hughes there after he had been shot down. Answering a question, the German said: “Without asking Hughes we knew all the types of the markers. So far as I know I got no more information from him than I got from other airmen. I have interrogated more than 1000 fliers.”

The hearing was adjourned.

Move your cursor over the image above to zoom.

Move your cursor over the image above to zoom.